When you hold a hot teapot, the heat you feel is a result of conduction. Conduction is the transfer of thermal energy from one object to another through direct contact. In this case, the hot teapot transfers heat to your hand when you touch it. The material of the teapot also plays a role in how much heat is conducted and how long the teapot stays hot. For example, cast iron teapots are known for their heat retention and conduction, while porcelain teapots are better at retaining heat.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Conduction | Heat is conducted from the hot teapot to your hand at the points where the two are in direct contact |

| Radiation | The hot outer surface of the teapot radiates heat into the air, heating it up |

| Convection | Convection currents are set up in the surrounding air around the teapot, the hot air rising above it and being replaced by colder air from below |

What You'll Learn

Conduction, convection, and radiation

When you hold a hot teapot, the heat transfer that occurs between the teapot and your hand is known as conduction. Conduction is the transfer of heat energy by direct contact. In this case, the heat from the hot teapot is transferred to your hand through physical touch.

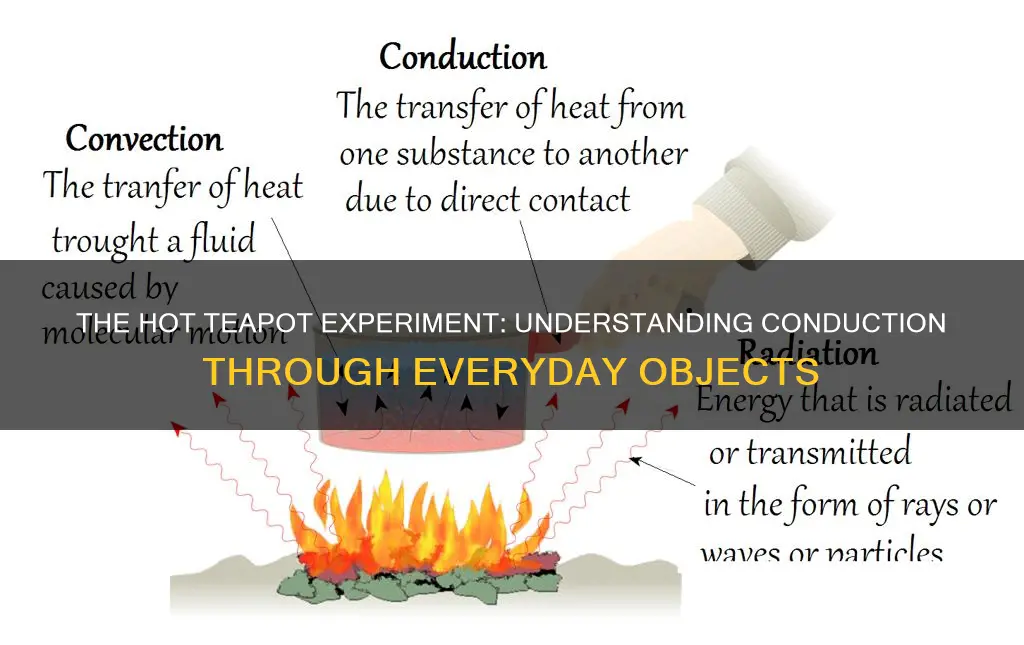

Now, let's delve into the three main methods of heat transfer: conduction, convection, and radiation.

Conduction

Conduction is the transfer of heat energy between objects in direct contact. It occurs due to the difference in temperature between the objects, with heat flowing from the hotter object to the colder one. This process happens through molecular collisions, where the higher-energy molecules collide with slower-speed molecules, increasing their kinetic energy. The rate of conduction depends on factors such as the temperature gradient, cross-section of the material, length of the travel path, and physical properties of the material.

Convection

Convection, on the other hand, is the movement of heat by the actual motion of matter. It occurs specifically in fluids (liquids or gases) and is driven by density differences. When a fluid is heated, it expands, becomes less dense, and rises, while the colder, denser fluid sinks. This creates convection currents, which transfer heat. A classic example of convection is a space heater, which heats the air near the floor, causing it to rise and be replaced by cooler air, creating a continuous cycle.

Radiation

Radiation is the transfer of heat energy without any physical contact between objects. It occurs through the emission of electromagnetic waves, which carry energy away from the emitting object. All objects with a temperature greater than absolute zero emit thermal radiation, with the amount of radiation increasing with temperature. Thermal radiation can travel through a vacuum or any transparent medium. The sun is a prime example of thermal radiation, transferring heat across the solar system.

Pots and Pans: Storage Essentials

You may want to see also

Materials with good heat retention

When you hold a hot teapot, the heat you feel is indeed due to conduction. Conduction is the transfer of heat from a warmer object to a cooler one, and in this case, the heat from the hot tea inside the teapot is transferred to your hand through the teapot's material.

Different materials have varying abilities to retain heat, and this property is crucial in the design of teapots to ensure that tea stays hot for a reasonable period. Here are some materials known for their good heat retention:

Clay: Clay teapots, such as those used in traditional Chinese tea ceremonies, are renowned for their heat retention properties. Clay is a popular choice for teapots because it effectively retains and gradually releases heat, keeping the tea warm for a more extended period. Additionally, unglazed clay teapots are known to absorb the flavors of the teas brewed in them over time, enhancing the flavor of subsequent brews.

Stoneware: Stoneware is another material that is excellent at retaining heat. It is often used in teapots, and its ability to maintain heat is considered superior to that of porcelain. Teapots made of stoneware help keep the tea warm for a more extended period, making them a practical choice for brewing and serving tea.

Sand: While not typically used for teapots, sand is worth mentioning due to its impressive heat retention capabilities. Sand has a low heat transfer coefficient, allowing it to retain heat for very long periods. This is why sand on a beach remains warm even after sunset in hot countries.

Polystyrene: Expanded polystyrene, a synthetic plastic polymer, is commonly used in construction as insulation due to its excellent heat retention properties. While not a conventional choice for teapots, polystyrene's ability to retain heat for extended periods is noteworthy.

Air: Air is an interesting example of a substance that can retain heat for a surprisingly long time. When heated, air can hold onto that heat for many hours, which is why our houses stay warm even after the central heating turns off. This property of air is essential in maintaining a comfortable indoor temperature.

Hard Anodized Pans: Safe or Not?

You may want to see also

The human pain threshold

When you hold a hot teapot, the heat is transferred from the metal of the teapot to your skin through conduction. The teapot's metal conducts heat well, and your pain threshold for heat will determine how long you can hold it.

The threshold of pain, or pain threshold, is the point at which a person or animal begins to feel pain in response to a stimulus. It is a subjective phenomenon that varies from individual to individual and can change for a given individual over time. The threshold of pain is often defined as the minimum intensity of a stimulus that is perceived as painful. However, it is important to distinguish between the stimulus, which can be directly measured, and the person's resulting pain perception, which is internal and subjective. The intensity at which a stimulus begins to evoke pain is called the threshold intensity.

Pain, at its most basic level, is an alarm signal indicating potential damage to the body. The pain threshold is the point at which discomfort transitions into pain. For example, clamping a person's wrist would not initially cause pain, but as the pressure increases, it would cause discomfort, and eventually pain. The level of tightness that elicits a pain response is that person's pain threshold pressure.

While there is no definitive threshold for pain in humans, researchers estimate that the maximum pain a human can endure is somewhere above 11 dol, a unit of measurement for pain based on the Latin word "dolor" (pain). This scale was devised by researchers at Cornell University, who burned their research subjects' foreheads for three seconds at a time, over 100 times, and asked them to report their pain levels. Many of the subjects reported feeling an 8 on the pain scale, and any measurement of pain above 11 dols was deemed "indiscernible" due to being too unbearable to quantify.

Physical, psychological, and genetic factors all play a role in the subjective perception of pain, making precise quantification and comparison challenging. For instance, individuals who have experienced more physical injuries may develop a higher tolerance for pain. Additionally, the brain's perception of pain can influence how much pain a person can tolerate. If the brain believes there is no pain, the person may stop feeling pain, which is known as the placebo effect.

Hand-Tossed Pizza: Better Taste, Better Texture

You may want to see also

The thermal equilibrium of tea

When you hold a hot teapot, the heat transfer from the teapot to your hand is an example of conduction. Conduction is the transfer of thermal energy between objects in direct contact. The material of the teapot, such as thin steel or stainless steel, is a good conductor of heat, which is why the teapot feels hot to the touch.

Now, let's discuss the thermal equilibrium of tea:

When you brew a cup of tea, you typically start by boiling water in a kettle or teapot. During this process, you are adding thermal energy to the water, increasing its temperature. Once the water reaches its boiling point, you might let it cool down slightly before pouring it over the tea leaves or herbal mix in your teapot. At this point, the water is in a state of thermal equilibrium, where its temperature remains relatively constant.

However, as soon as you pour the hot water into the teapot, the thermal equilibrium is disrupted. The teapot, the air in the room, and even the tea leaves themselves are at lower temperatures than the boiling water. As a result, the water starts to lose heat to its surroundings. This heat transfer continues until the water, the teapot, the air, and the tea leaves all reach the same temperature, restoring thermal equilibrium.

The time it takes for the tea to reach thermal equilibrium depends on various factors, including the material of the teapot, the volume of water, the temperature of the surroundings, and the presence of any insulating covers, like a tea cosy. For example, a clay teapot tends to retain heat very well, while a stainless steel teapot might cool down faster.

Once the tea reaches thermal equilibrium, it doesn't mean that the temperature will remain constant forever. Over time, the tea will continue to lose heat to the surrounding environment, especially if the teapot is not insulated. This gradual loss of heat will cause the tea's temperature to decrease until it eventually reaches the same temperature as the room, at which point the tea is considered to have cooled down.

To maintain the desired temperature of the tea, it is essential to consider the principles of thermal equilibrium. By using appropriate materials for the teapot, such as clay or porcelain, and implementing insulation methods like tea cosies, the rate of heat loss can be minimised, allowing you to enjoy your tea at the ideal temperature for a more extended period.

Defrost Your Fridge the Natural Way: The Hot Pot Method

You may want to see also

The history of the teapot

Origins in China

The earliest teapots are believed to have emerged in China around 1500 AD, with the development of Yixing teapots. These teapots were crafted using purple and red clay from Yixing in the eastern province of Jiangsu, and featured the handle and spout design that we still recognise today. The Yixing teapots were small, intended for individual consumption, and allowed for a higher ratio of leaves to water, giving the brewer greater control over the brewing process. This enabled the creation of multiple small infusions, each with unique flavour profiles. The clay used in Yixing teapots is also porous, allowing the teapot to absorb the smell and flavour of the tea over time, enhancing the flavour of subsequent brews.

From East to West

The spread of Yixing teapots from China to other parts of Asia, including Japan, Burma, Sumatra, and Java, not only influenced the evolution of teapot designs but also spurred the development of hard-paste porcelain in the Western world. In the 17th century, tea and teapots began to be exported from China to Europe as part of the trade in exotic spices and luxury goods. These early Chinese teapots were made of porcelain, which could withstand the seawater during the long voyage. The European upper classes, who were the primary consumers of tea at the time, favoured these imported Chinese teapots over the fragile European earthenware, which often cracked or exploded when filled with boiling water.

European Innovations

It wasn't until the 18th century that European potteries in Holland, Germany, and England began to create their own teaware. Initially, they imitated the Chinese teapot designs, but soon began to experiment with new shapes and materials. The pear-shaped, or pyriform, teapot was one of the first major deviations from the traditional Chinese style, becoming popular during the reign of Queen Anne. Other popular shapes included the "globular" style, resembling a sphere on a raised foot, and the vase or urn style, harkening back to the wine-pot origins of the teapot.

Mass Production and Novelty Designs

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, teapots entered the era of mass production. James Sadler's "Rockingham Brown" teapots, also known as "Brown Betty", became a fixture in most British households by the late 1880s. The 20th century saw the teapot evolve into a design icon, with artists like Peter Shire creating bold and whimsical teapot sculptures. Today, the teapot continues to be an essential part of tea culture around the world, with various materials, shapes, and designs available to suit different brewing techniques and aesthetic preferences.

Pork Chops: Perfect Pan-Searing Techniques

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, when you hold a hot teapot, the heat is being conducted from the hot water inside the teapot to the metal of the teapot and then to your hand.

Conduction is the transfer of heat from one object to another through direct contact.

Metals are good conductors of heat, with silver having the highest thermal conductivity of any metal. Other materials that conduct heat well include clay, ceramic, and cast iron.

You can use a tea cosy, which is a thermally insulating cover that goes over the teapot to slow down the transfer of heat. You can also use a tea warmer, which is a stand with a tea candle that keeps the teapot warm from below.

This could be due to the design of the spout. Making the outside surface of the spout more hydrophobic and reducing the radius of curvature at the inside tip of the spout can help to avoid dribbling.